A World Without Email

I’ve been a fan of Cal Newport’s previous writing about building career capital and doing deep work. Since implementing his time-block planning system, my personal productivity has increased 2-3x at least. So I was very excited to read his 2021 book A World Without Email. Where much of Newport’s previous work focused on individual productivity, this new book examines the entire knowledge work enterprise and how it can be improved.

The Hyperactive Hive Mind

Since the rise of email in the workplace (and it’s siblings like Slack or Microsoft Teams), we office drones have become ever more harried by the demands of constant connection. Always-on work is simultaneously addicting and stressful. This manner of communicating is what Newport terms the hyperactive hive mind.

The hyperactive hive mind wasn’t planned. Nobody sat down and decided this was the most efficient way to work. It’s an emergent property of the combination of human evolutionary biology and the features of the technology in question.

Humans are social creatures. In our evolutionary environment, reproductive chances were helped tremendously by staying on good terms with the tribe. People who were disliked could end up shunned; and shunned people would probably die in the wilderness before reproducing. This evolutionary pressure created humans who seek to maintain connection. We’re anxious about missing or ignoring requests from our “tribe”, because in eons past that could be the difference between life and death.

Now consider a communications medium like email or chat. These tools bring the marginal cost of sending a message to near-zero. And it’s easy to loop in numerous participants, whether the message is really useful to them or not. The economics of the tools result in a dramatic increase of sent (and by extension, received) messages, far beyond anything our species has previously experienced.

Combine our human need to stay connected with tools that turn up the volume of communications to 11, and you’ve got the hyperactive hive mind: an environment of constant emailing and chatting that stresses us out, but from which we can’t extract ourselves. We’re trapped in an inadequate equilibrium, with no one person empowered to unilaterally escape. It’s become the default way to do knowledge work—not because it’s best, but because it’s what happens naturally when everyone follows immediate short-term incentives.

But the hyperactive hive mind isn’t only emotionally distressing—it’s also a barrier to greater value creation.

Attention Capital Theory

A century ago, physical capital was the primary asset to successfully deployed to maximize production. Labor was cheap and interchangeable—factory equipment was not. So came improvements centered around the deployment of capital. Where once you had individual craftsmen putting together entire products one-by-one, you now had explicit and efficient workflows enabled by machines and assembly lines.

Physical capital is no longer the main driver of value creation in the contemporary knowledge work economy—brains are. Hence the attention capital theory: a knowledge work business needs to deploy brain-power optimally to best compete in the market. If a firm’s brain-power is fractured by the hyperactive hive mind—constantly pulled in a million different directions—then the firm is wasting valuable resources.

Of course, brains can’t be organized like machines in a factory.1 Peter Drucker wrote in his 1967 book The Effective Executive that knowledge workers can’t be directed like factory workers—they must direct themselves. You can give a factory worker precise instructions to build a widget, but you cannot give a scientist precise instructions to cure cancer. Knowledge work requires thought and creativity, and you cannot extract their products on demand.

But Newport argues that this is not entirely accurate. There are many aspects of knowledge work which do not require gifts from the Muse (e.g., the book’s eponymous email), and these aspects ought to be standardized within a business. We must separate knowledge work (cannot be directed) from workflows (can be directed). By clarifying how knowledge work is organized, workers can direct more of their attention to value-producing mental efforts over wasteful ad hoc administration.

Doing Better Than Default

Any system can do better than the hyperactive hive mind if it has two qualities:

- Minimizes context switching

- Minimizes communication overload

The human mind works best when working on one thing at a time, pulling all relevant information into working memory. Switching back and forth between unrelated tasks results in dumping and recalling all of that mental context again and again. This is expensive in terms of time and mental energy. If you’re constantly checking email for new messages, you’re engaged in endless context switching; your ability to focus on hard work is greatly diminished.

Of course, part of the reason that you’re constantly context switching to inbound communications is that they are incessant and demanding! You never know if the latest Ping! is an “urgent” request to drop everything and do something else—better check it to be safe!2 Minimizing context switching thus requires getting inbound messages under control as well.

Newport spends the rest of the book covering a number of strategies for reducing context switching and structuring communication to avoid overload.

Workflows

Structured workflows help to safeguard the time needed to work on tasks requiring concentration. They reduce back-and-forth by setting clear expectations of who is doing what and when they are doing it.

Task Boards

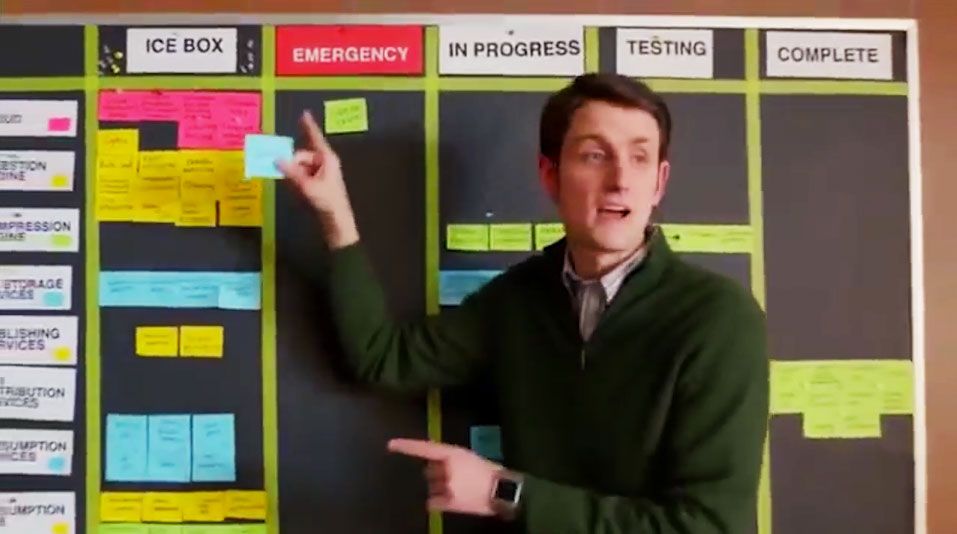

Task boards are a simple way to visually keep track of work to be done in a project. You have a board divided into columns—at its simplest, 1) To Do, 2) Doing, and 3) Done—and cards in those columns representing tasks. As work is picked up and completed, the card representing it moves from column to column. This makes it easy to know what needs to be done, what’s happening now, and what is complete.

You can customize task boards to represent whatever information you need. Maybe you add a Blocked column for work that’s stuck until some other thing can happen. Maybe you further divide the board into rows representing your team members or different subcomponents of a project. Experiment to find the right format for you.

Status Update Meetings

A foundational idea in agile methodology is that short meetings held on a regular schedule are by far the best way to review and update task boards.

Rather than ad hoc, back-and-forth messages about the status of work, schedule regular short status updates. The typical variation used in the Scrum agile workflow is the daily stand-up: the team stands up (standing discourages going long), and everyone says 1) what they did yesterday, 2) what they are stuck on, and 3) what they plan to do today. If an issue comes up that’s going to require more time than the short status meeting, schedule it for later—don’t let the meeting run long, or it wastes everyone’s time.

Automation

While I’d happily replace my working self with Tombot9000, that’s not what Newport is talking about here. Rather, the automation step is about breaking down workflows and organizing a clear system around it. Think of an explicit routine shared by a group. You don’t have to think about routines—you execute them near-automatically. There are three steps to building this kind of workflow automation:

- Partitioning: divide workflows into discrete steps. (What must be accomplished? Who is responsible?)

- Signaling: have a system to track which phase of the workflow a piece of work is in. Workers can check this system to see what is ready for them to work on.

- Channeling: clarity around how/where deliverables are handled. (E.g., when I finish my work on X, I will put it in this agreed upon shared Dropbox folder.)

Whether you’re deploying complex automation or just following handcrafted procedures, these processes will reduce your dependence on the hyperactive hive mind workflow and reward you with extra cognitive energy and mental peace. Make automatic what you can reasonably make automatic, and only then worry about what to do with what remains.

Protocols

Whether implicit or formal, many office activities are structured by some manner of rules.

In case you didn’t know that Cal Newport’s day job is “computer scientist”, this section of the book will let you know. Rather than summarize Newport’s history of information theory, I’ll skip to the conclusion: communication can be made clearer and shorter with more defined protocols. In the absence of protocols, you get the hyperactive hive mind shooting messages in all directions all the time. But with clear rules, you can get that under control. Some example protocols you can employ:

- Office hours: block off times when it’s publicly known you are free to talk and help with whatever. If it’s not office hours, come back later.

- Don’t send emails back-and-forth to schedule meetings; use a service like Calendly instead.

- Meetings should be structured to keep them focused and short. Have an agenda.

- Apply protocols to outside communications too. When working with clients, make is clear what ways in which you are available.

With protocols, you’re making a trade-off between cognitive cycles used and convenience. Protocols will probably slow down some amount of information and will make certain tasks slower. But done well, the inconvenience cost will be dwarfed by the cognitive cycles savings.

Specialization

Knowledge workers with highly trained skills, and the ability to produce high-value output with their brains, spend much of their time wrangling with computer systems, scheduling meetings, filling out forms, fighting with word processors, struggling with PowerPoint, and of course, above all, sending and receiving digital messages from everyone about everything at all times.

Many business have used the cost savings of digital tools to reduce support costs. Why hire a secretary to file the salesman’s expense reports when you can tell him to upload pictures of receipts on a web portal? But this line of thinking has gone so far that many people are bogged down with a plethora of just-easy-enough administrative tasks.

Newport’s suggestion: hire more support staff. While this sounds pricey, consider that the tasks you’ll be moving to these support staff are currently being done by expensive experts and executives. Why do you want a six-figure rockstar programmer spending an hour on TPS reports, when they could be adding multiples of that hour’s cost to your bottom line by doing their actual job?

Of course, support staff aren’t cannon fodder. They too benefit from the structures mentioned earlier. Their workflows should be considered when expanding their capacity.

Closing Thoughts

A World Without Email identifies the problems with electronic communication in contemporary office work and offers constructive remedies. I’m hopeful that we’ll see more attempts to implement sane workflows rather than completely unstructured messaging.

I can’t help but analogize the situation to the use of application programming interfaces (APIs) in coding. APIs are standardized ways for programs to communicate with other programs. It would get messy and brittle for my code to reach directly inside your code to do a thing—I don’t understand how or why you wrote your functions like you did, and small changes could break things. But an API makes a promise: if you make requests that look like this, I will reliably respond like this. Using the API, I can treat your underlying code like a black box. If I make requests in a specific way, I’ll get the desired outputs.

Email and chat are like programming without APIs. It’s the equivalent of reaching directly into someone’s mind to dump some piece of work there. Both requests and responses are unpredictable in time and form. Everyone wastes time trying to make sense of it all. The office needs a sort of human API—formal rules about how you can work with each other to make things more reliable. I don’t need to understand how you perform your work—I just need to know how to format my requests to you such that I get the outputs I need.

Footnotes

-

It gets messy—brains don’t work so well when spread across a concrete floor. ↩

-

Though Newport is only addressing technologies like email in this book, it’s worth considering non-technological impediments to focus. Consider the pre-pandemic trend toward open floor plan offices. If a Ping! from your phone is enough to derail your concentration, then listening to all your nearby coworkers’ conversations must be just as bad. Even though I’ve got the luxury of an office door, I still usually blast heavy metal through noise-cancelling headphones to block out distracting environmental noise. ↩