Web Scraping with Deno

This article was originally published on the This Dot blog.

Maybe you’ve had this problem before: you need data from a website, but there isn’t a good way to download a CSV or hit an API to get it. In these situations, you may be forced to write a web scraper. A web scraper is a script that downloads the HTML from a website as though it were a normal user, and then it parses that HTML to extract information from it. JavaScript is a natural choice for writing your web scraper, as it’s the language of the web and natively understands the DOM. And with TypeScript, it is even better, as the type system helps you navigate the trickiness of HTMLCollections and Element types.

You can write your TypeScript scraper as a Node script, but this has some limitations. TypeScript support isn’t native to Node. Node also doesn’t support web APIs very well, only recently implementing fetch for example. Making your scraper in Node is, to be frank, a bit of a pain. But there’s an alternative way to write your scraper in TypeScript: Deno!

Deno is a newer JavaScript/TypeScript runtime, co-created by one of Node’s creators, Ryan Dahl. Deno has native support for TypeScript, and it supports web APIs out of the box. With Deno, we can write a web scraper in TypeScript with far fewer dependencies and boilerplate than what you’d need in order to write the same thing in Node.

In this blog, we’re going to build a web scraper using Deno. Along the way, we’ll also explore some of the key advantages of Deno, as well as some differences to be aware of if you’re coming from writing code exclusively for Node.

Getting Started

First, you’ll need to install Deno. Depending on your operating system, there are many methods to install it locally.

After installation, we’ll set up our project. We’ll keep things simple and start with an empty directory.

mkdir deno-scraper

cd deno-scraperNow, let’s add some configuration. I like to keep my code consistent with linters (e.g. ESLint) and formatters (e.g. Prettier). But Deno doesn’t need ESLint or Prettier. It handles linting and formatting itself. You can set up your preferences for how to lint and format your code in a deno.json file. Check out this example:

{

"compilerOptions": {

"noUnusedLocals": true,

"noUnusedParameters": true,

"noUncheckedIndexAccess": true

},

"fmt": {

"options": {

"useTabs": true,

"lineWidth": 80,

"singleQuote": true

}

}

}You can then lint and format your Deno project with deno lint and deno fmt, respectively.

If you’re like me, you like your editor to handle linting and formatting on save. So once Deno is installed, and your linting/formatting options are configured, you’ll want to set up your development environment too.

I use Visual Studio Code with the Deno extension. Once installed, I let VS Code know that I’m in a Deno project and that I’d like to auto-format by adding a .vscode/settings.json file with the following contents:

{

"deno.enable": true,

"editor.formatOnSave": true,

"editor.defaultFormatter": "denoland.vscode-deno"

}Writing a Web Scraper

With Deno installed and a project directory ready to go, let’s write our web scraper! And what shall we scrape? Let’s scrape the list of Deno 3rd party modules from the official documentation site. Our script will pull the top 60 Deno modules listed, and output them to a JSON file.

For this example, we’ll only need one script. I’ll name it index.ts for simplicity’s sake. Inside our script, we’ll create three functions: sleep, getModules and getModule.

The first will give us a way to easily wait between fetches. This will prevent issues with our script, and the owners of the website we’ll contact, because it’s unkind to flood a website with many successive requests. This type of automation could appear like a Denial of Service (DoS) attack, and could cause the API owners to ban your IP address from contacting it. The sleep function is fully implemented in the code block below. The second function (getModules) will scrape the first three pages of the Deno 3rd party modules list, and the third (getModule) will scrape the details for each individual module.

// This sleep function creates a Promise that

// resolves after a given number of milliseconds.

async function sleep(milliseconds: number) {

return new Promise(resolve => {

setTimeout(resolve, milliseconds);

});

}

async function getModules() {

// ...

}

async function getModule(url: string | URL) {

// ...

}Scraping the Modules List

First, let’s write our getModules function. This function will scrape the first three pages of the Deno 3rd party modules list. Deno supports the fetch API, so we can use that to make our requests. We’ll also use the deno_dom module to parse the HTML response into a DOM tree that we can traverse.

Two things we’ll want to do upfront: let’s import the deno_dom parsing module, and create a type for the data we’re trying to scrape.

import { DOMParser } from 'https://deno.land/x/deno_dom/deno-dom-wasm.ts';

interface Entry {

name?: string;

author?: string;

repo?: string;

href?: string;

description?: string;

}Next, we’ll set up our initial fetch and data parsing:

async function getModules() {

// Here, we define the base URL we want to use, the number

// of pages we want to fetch, and we create an empty array

// to store our scraped data.

const BASE_URL = 'https://deno.land/x?page=';

const MAX_PAGES = 3;

const entries: Entry[] = [];

// We'll loop for the number of pages we want to fetch,

// and parse the contents once available

for (let page = 1; page <= MAX_PAGES; page++) {

const url = `${BASE_URL}${page}`;

const pageContents = await fetch(url).then(res => res.text());

// Remember, be kind to the website and wait a second!

await sleep(1000);

// Use the deno_dom module to parse the HTML

const document = new DOMParser().parseFromString(pageContents, 'text/html');

if (document) {

// We'll handle this in the next code block

}

}

}Now that we’re able to grab the contents of the first three pages of Deno modules, we need to parse the document to get the list of modules we want to collect information for. Then, once we’ve got the URL of the modules, we’ll want to scrape their individual module pages with getModule.

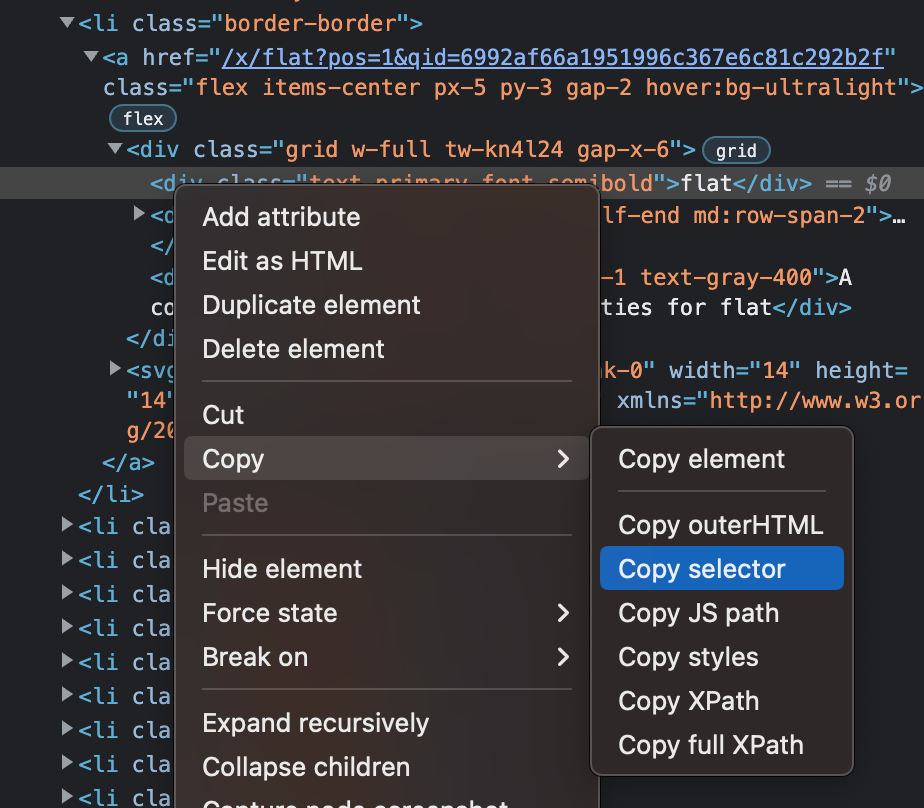

Passing the text of the page to the DOMParser from deno_dom, you can extract information using the same APIs you’d use in the browser like querySelector and getElementsByTagName. To figure out what to select for, you can use your browser’s developer tools to inspect the page, and find selectors for elements you want to select. For example, in Chrome DevTools, you can right-click on an element and select “Copy > Copy selector” to get the selector for that element.

if (document) {

// Conveniently, the modules are all the only <li> elements

// on the page. If you're scraping different data from a

// different website, you'll want to use whatever selectors

// make sense for the data you're trying to scrape.

const modules = document.getElementsByTagName('li');

for (const module of modules) {

const entry: Entry = {};

// Here we get the module's name and a short description.

entry.name = module.querySelector(

'.text-primary.font-semibold',

)?.textContent;

entry.description = module.querySelector(

'.col-span-2.text-gray-400',

)?.textContent;

// Here, we get the path to this module's page.

// The Deno site uses relative paths, so we'll

// need to add the base URL to the path in getModule.

const path = module

.getElementsByTagName('a')[0]

.getAttribute('href')

?.split('?')[0];

entry.href = `https://deno.land${path}`;

// We've got all the data we can from just the listing.

// Time to fetch the individual module page and add

// data from there.

let moduleData;

if (path) {

moduleData = await getModule(path);

await sleep(1000);

}

// Once we've got everything, push the data to our array.

entries.push({ ...entry, ...moduleData });

}

}Scraping a Single Module

Next we’ll write getModule. This function will scrape a single Deno module page, and give us information about it.

If you’re following along so far, you might’ve noticed that the paths we got from the directory of modules look like this:

/x/deno_dom?pos=11&qid=6992af66a1951996c367e6c81c292b2fBut if you navigate to that page in the browser, the URL looks like this:

https://deno.land/x/deno_dom@v0.1.36-alphaDeno uses redirects to send you to the latest version of a module. We’ll need to follow those redirects to get the correct URL for the module page. We can do that with the redirect: 'follow' option in the fetch call. We’ll also need to set the Accept header to text/html, or else we’ll get a 404.

async function getModule(path: string | URL) {

const modulePage = await fetch(new URL(`https://deno.land${path}`), {

redirect: 'follow',

headers: {

Accept: 'text/html',

},

}).then(res => {

return res.text();

});

const moduleDocument = new DOMParser().parseFromString(

modulePage,

'text/html',

);

// Parsing will go here...

}Now we’ll parse the module data, just like we did with the directory of modules.

async function getModule(path: string | URL) {

// ...

const moduleData: Entry = {};

const repo = moduleDocument

?.querySelector('a.link.truncate')

?.getAttribute('href');

if (repo) {

moduleData.repo = repo;

moduleData.author = repo.match(

/https?:\/\/(?:www\.)?github\.com\/(.*)\//,

)![1];

}

return moduleData;

}Writing Our Data to a File

Finally, we’ll write our data to a file. We’ll use the Deno.writeTextFile API to write our data to a file called output.json.

async function getModules() {

// ...

await Deno.writeTextFile('./output.json', JSON.stringify(entries, null, 2));

}Lastly, we just need to invoke our getModules function to start the process.

getModules();Running Our Script

Deno has some security features built into it that prevent it from doing things like accessing the file system or the network without granting it explicit permission. We give it these permissions by passing the --allow-net and --allow-write flags to our script when we run the script.

deno run --allow-net --allow-write index.tsAfter we let our script run (which, if you’ve wisely set a small delay with each request, will take some time), we’ll have a new output.json file with data like this:

[

{

"name": "flat",

"description": "A collection of postprocessing utilities for flat",

"href": "https://deno.land/x/flat",

"repo": "https://github.com/githubocto/flat-postprocessing",

"author": "githubocto"

},

{

"name": "lambda",

"description": "A deno runtime for AWS Lambda. Deploy deno via docker, SAM, serverless, or bundle it yourself.",

"href": "https://deno.land/x/lambda",

"repo": "https://github.com/hayd/deno-lambda",

"author": "hayd"

}

// ...

]Putting It All Together

Tada! A quick and easy way to get data from websites using Deno and our favorite JavaScript browser APIs. You can view the entire script in one piece on GitHub.

In this blog, you’ve gotten a basic intro to how to use Deno in lieu of Node for simple scripts, and have seen a few of the key differences. If you want to dive deeper into Deno, start with the official documentation. And when you’re ready for more, check out the resources available from This Dot Labs at deno.framework.dev, and our Deno backend starter app at starter.dev!